“This is the end of fashion as we know it,” said Lidewij (Li) Edelkoort in her Anti-Fashion Manifesto. Fashion is disposable like condoms; it lacks innovation, which Edelkoort— one of fashion’s most accredited trend forecasters— credits to a need for speed.

The past century, with its technological innovation and consumer culture, gave way to the concept of fast fashion: the expediting of cheap clothing at a quick rate in order to provide high fashion trends to the general public. The topic has been talked about for its economic marvels, environmental and humanitarian pitfalls and uncertain impact on the future of the industry.

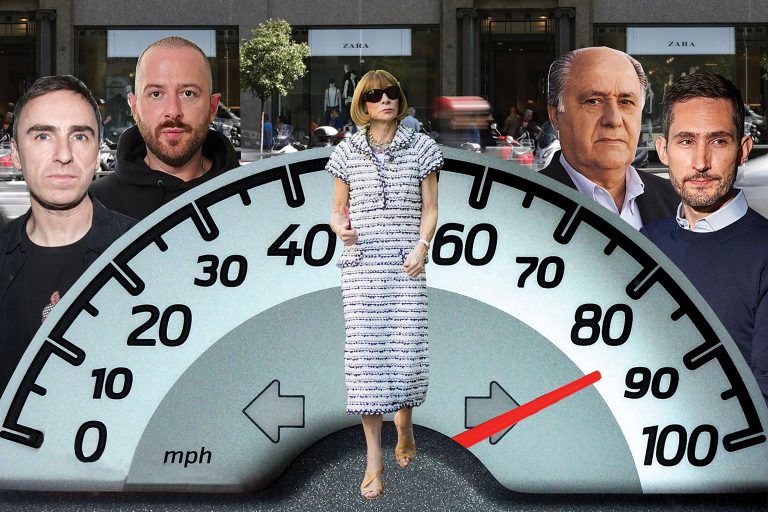

But what is scarcely mentioned is the influence of fast fashion on luxury: how it affects trend turnover and creative innovation. Fast fashion originated to chase and recreate luxury trends, but it seems its role has been refigured. Now luxury brands struggle to keep up with the trend turnover set in place by fast fashion.

According to a report by the Business of Fashion in 2017, fast fashion sales have increased by more than 20% in the past three years. Consumers have grown reliant on the constant influx of clothing. A study done for the Huffington Post revealed that fast fashion pioneer Zara receives two shipments of new products a week, while H&M and Forever 21 drop new releases everyday. Because of this, high end brands feel pressure to follow the rapid rate of production in order to appease the consumers’ new expectations.

Leading high fashion brands move towards accelerating the process from design to market. For instance, Gucci announced in 2017 its plan to focus on supply chain optimisation and responsiveness, as was noted in the same report done by BOF.

Because of the exponential pace at which it can deliver information, social media is also responsible for the shift to a consumer-centric business model. Trends were once communicated monthly by Vogue but are now distributed by the hour via Instagram. Thousands of temporarily relevant opinions undermine Anna Wintour’s once overarching voice on what is and is not fashion.

A study for the Huffington Post concluded that 35% of millennial women in America say social media is one of the top influences when making clothing purchases. The same study reported that 33% of women considered clothes old after wearing them three or less times. With this combination of influence and demand for rapid replacement, it is no wonder why fast fashion is picking up the industry’s pace.

“Speed is everything right now,” said Karin Tracey in an article on luxury fashion market speed for Digiday. Tracey is the head of fashion, luxury and beauty for Facebook. “For luxury brands, whoever is the fastest right now will have competitive advantage, full stop. They need to step out of the comfort zone of perfection, think about how to move fast and build things to let them do so.” In this context, a fashion brand’s success is based on its capability to blend design and production efficiently enough to produce at a rate approximate to that of fast fashion.

But for luxury, that manufacturing speed is impossible. Fashion houses are forced to compete against factories of mass production when the two should not even exist in the same bracket of competition. “The whole industry runs so fast because we need to deliver something new to the store every two weeks so the client isn’t bored,” said Demna Gvasalia of Vetements and Balenciaga in an article for Well Made Clothes. “They don’t want to wait for six months, so we have the pre-collection, the pre-pre-collection, and the main collection, which nobody is buying, so it all just ends up on a sales rack.”

A maximum of six collections a year cannot compete with weekly micro-collections produced in fast fashion. There is an incongruence in trend delivery that plays to luxury’s disadvantage. In the beginning there were two fashion seasons: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter. Traditionally, Fall/Winter is shown in Spring and vice versa. That is a six month waiting period before collections are available for purchase. And within that period of time, fast fashion brands impose an impending threat to rip off runway trends and manufacture them before high end collections hit retail. The climate is instantaneous, and seasonal turn-around is no longer effective.

The quality between fast fashion and luxury is obviously distinguishable, but that is irrelevant to the average consumer, who just wants to appear to be “in fashion.” This is another problem: the term fashion has lost its meaning. It has become a way of saying something is cool or trendy; the clothes are no longer addressed with anything other than an expiration date.

“When you do six shows a year, there’s not enough time for the whole process,” said Raf Simons, chief creative director at Calvin Klein, in an article for Well Made Clothes. “[You] have no incubation time for ideas, and incubation time is very important.When you try an idea, you look at it and think, Hmm, let’s put it away for a week and think about it later. But that’s never possible when you have only one team working on all the collections.” These sentiments relate strongly to Simon’s departure from the House of Dior in 2015 in order to escape the high pressure and fast paced environment.

Fashion designers are grounded in individualism but expected to create for the masses. Cristobal Balenciaga and Yves Saint Laurent — they were innovators. Alexander Mcqueen and John Galliano — they were visionaries. But there is no time for that anymore. “With this lack of conceptual innovation,” says Li Edelkoort, “the world is losing the idea of fashion.”

Written by Kat Sours

Graphic by Max Condon